I did not know there was an actual ping pong ball at the top of Charles’s Prince of Wales coronet. But neither, reportedly, did Charles. This major gap in my royal jewelry knowledge was exposed at my recent panel discussion on the subject at the 92nd Street Y. Mahnaz

Ispahani Bartos, a scholar of modern jewelry design, revealed that shehas one of the original 1969 Electroform models of Charles’s head in her private collection and confirmed during the lecture that the orb at the top of Louis Osman’s radical design was in fact exactly what you would hit around in a game of table tennis (albeit, layered in gold).

How the ping pong ball came to be there is but one chapter in the history of perhaps the most modern of royal jewels, celebrating its 50th anniversary this month.

A PRINCE IN SEARCH OF A CROWN

Two months shy of his 21st birthday, Prince Charles was ready for his investiture as the Prince of Wales in 1969. All he needed was a crown. There was one, of course, the single arched silver gilt Coronet of George, but when the Duke of Windsor ran away from his kingdom in 1936, he also ran away with this crown.

Yes, that was officially illegal, but the Queen Mother would rather make a new coronet for Charles if getting the original one back meant she had to talk to Wallis or Edward again. (It did eventually make it back to the Tower of London after Edward’s death in 1972 and now sits there along with the other Defunct Coronet, that of Prince Frederick.) The search for Charles’s investiture crown began.

A SPACE AGE CORONATION

“Something that is modern,” is how the coronet has been described, and it was exactly what was needed. The late 1960s was a delicate time for the monarchy. “There were labor protests in England,” points out Ispahani Bartos, who is the founder and principal of Mahnaz Collection, a gallery known for original and artist jewels from the 1960s onwards. “There were power outages throughout the country, an oil shortage, uprisings in Wales, the troubles have started in Ireland. They wanted to do something slightly lower key and something in keeping with the mood of the time.”

An initial proposal by crown jeweler Garrard was rejected as overly extravagant and ostentatious. Enter Louis Osman.

Osman, explains Ispahani Bartos (who has studied English jewelry of the 1960s and 70s extensively and curated an exhibit called The London Originals last year) was “a maverick and a visionary. He didn’t adhere to any particular style. And he worked in many different forms. He was an architect, a sculptor, an arts patron and historian, and a jeweler. He was a highly unusual person, not a great businessman, and was known to never be on time.”

In Osman’s obituary in The Independent, April 1996, one friend described him as “the original hippie,” another as “the most creative man” he had ever met.

Osman had strong ties to the Worshipful Company of Goldsmith’s, more commonly known as the Goldsmiths' Company, and one of the Twelve Great Livery Companies of the City of London, which received its first royal charter in 1327. It is they who would gift the coronet to the royal family for Charles’s investiture—and they who commissioned Louis Osman to create it.

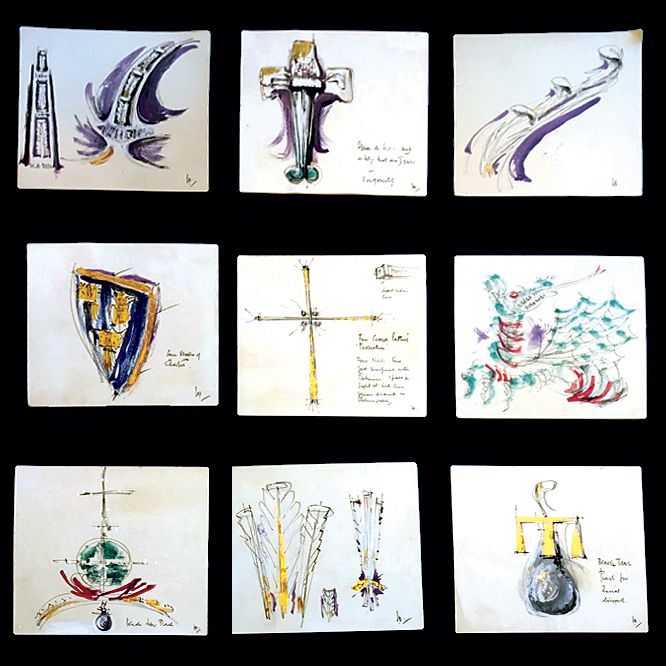

Osman’s sketches reveal his process. All the drawings represent the intention to create something streamlined, architectural, abstract rather than decorative, with strong lines. “Everything that might be decorative had a function, very much in line with modernist thinking,” says Ispahani Bartos, who now owns many of Osman’s original sketches. One design, never used, included a large black pearl under the orb to symbolize the pain of prevailing social disharmony. When the final sketch was agreed upon and approved Osman had about five months to deliver it.

A PING PONG BALL TO THE RESCUE

Osman’s vision was to create a coronet that would provide drama without too much weight, and meaning, but with modernity. The single arch of the coronet follows the form set down by King Charles II in 1677. The monde is inscribed with the Prince of Wales insignia and a plain cross. Diamonds on the monde are in the shape of the sign of Scorpio (Princes Charle’s birthday is November 14). At the base are four crosses and four fleur de lys in the last of the Welsh gold. They are decorated, albeit sparsely, with diamonds and emeralds.

The diamonds represent the seven deadly sins and the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit. Inside the coronet is a cap of purple velvet lined with ermine. The cap was likely to address Charles’s request for a coronet that could be worn by a modern Prince of Wales, without a wig, and with a regular haircut and “ears that show.”

The signs and symbols were all there in the coronet design yes, but Osman also fulfilled the desire—and the need— to make it new.

“The frame of the crown is quite abstract,” says Ispahani Bartos, “and the actual crosses and flowers are not made representationally, they too are abstract. Most modern of all of course was how the piece was actually made. Osman decided to try electroplating, a process that has never been attempted on such a large project, let alone a royal commission.”

Earlier crowns had been made by hammering solid sheets of precious metal or by casting. And earlier coronets had also not been as valuable. The Coronet of George was silver gilt and without stones. Louis Osman’s design would begin by taking a mold of the Prince’s head, creating a resin case and then layer it in gold to create a piece with major luster but much less weight. The final result weighed about three pounds. As with all experiments, along the way, there were learnings.

“Osman handmade a wax mold was then sent to Englehardt Industries in Gloucestershire—they were a manufacturer of precious metal solutions,” says Ispahani Bartos. “The first time they tried to electroform the coronet it was so delicate that when it went to be stamped, it broke apart. On the second try, after Osman made another mold, they got it right—almost. The orb however had not yet been successfully remade to Osman's very particular specifications. There was barely any time left before the investiture for Osman to complete his work on the coronet, so apparently a technician came up with the idea of trying to electroplate a ping pong ball. It worked.”

The ping pong coronet (or the “cuckoo clock coronet” as one royal official described it at the time) was seen throughout the world. Charles’s Prince of Wales Investiture ceremony, masterminded by Lord Snowdon, took place under a transparent canopy for a full view and was televised. The coronet was unlike any other royal jewel.

"Osman’s coronet has always been controversial,” says Ispahani Bartos. “Some love it, others hate it. I wonder how Prince Charles feels about it? Even more importantly, will it join the Crown Jewels?”

SIX DEGREES OF ELIZABETH TAYLOR

And what happened to Osman post-radical coronet? Goldsmiths Company again recommended him as the designer for a gift from the British government to the U.S government for the 1976 bicentennial. The gold, bejeweled, and enameled box Osman designed held an original copy of the Magna Carta for one year, and later a replica. It was on permanent display in the Rotunda until 2010.

Osman continued to make jewelry for his wife and friends, and sold pieces whenever he needed money. Elizabeth Taylor came with her then husband, Jack Warner, to Canons Ashby, where Louis and his wife Dilys Osman (an enamelist whose own work can be seen on Charles’s coronet) lived and worked.

“Taylor loved a rough, textured silver and turquoise modernist cuff belonging of Dilys, made in 1968, and she bought it," says Ispahani Bartos. "It ended up in the Christies sale of her jewels, not valued very highly."

Goldsmiths Hall continued their special relationship with Osman and recommended him for many commissions. In 1971 they devoted an exhibition to his all his works in gold and included his coronet for Prince Charles. Then head of the Goldsmiths Graham Hughes called it “deservedly the best known piece of new British gold of this century.”

And likely the only one of any century to include a ping pong Ball.

Editor-in-Chief Stellene Volandes is a jewelry expert, and the author of Jeweler: Masters and Mavericks of Modern Design (Rizzoli).